I Left My Socks on Mars Book

'Curiosity' (US 2014): Mars Rover Book Excerpt

Rod Pyle is an award-winning author and documentary filmmaker, and a contributor to Space.com as well. His previous books include "Destination Moon" (Smithsonian, 2005), "Missions to the Moon" (Sterling, 2009) and "Destination Mars" (Prometheus Books, 2012). He contributed this article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights .

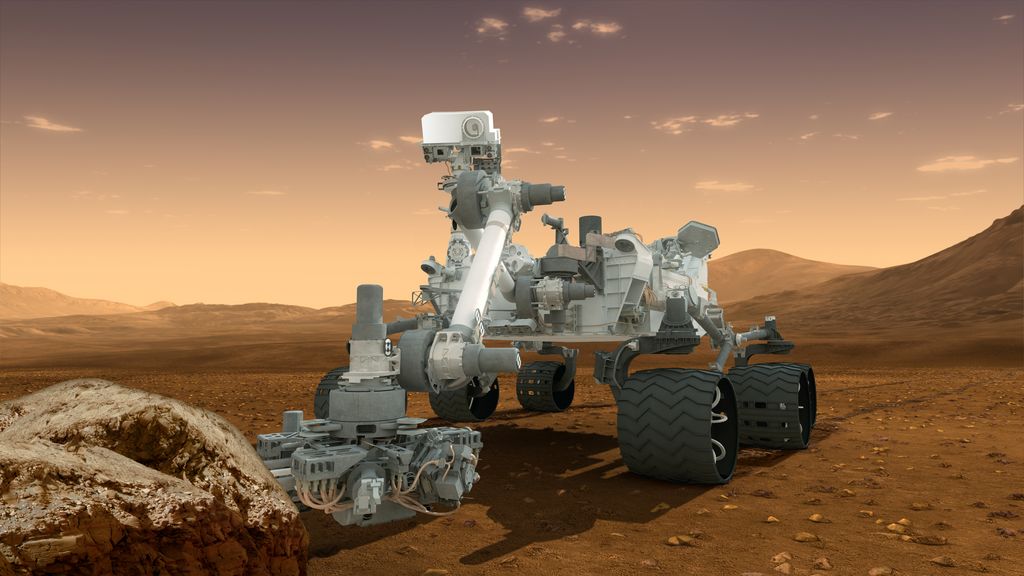

NASA's 1-ton Curiosity rover has been chugging across the surface of Mars for more than two years, reshaping scientists' understanding of the Red Planet as it goes.

The six-wheeled robot's main task is to determine if Mars has ever been capable of microbial life. The mission team has already checked that box, finding that a site called Yellowknife Bay was a habitable lake-and-stream system billions of years ago. Curiosity is now cruising toward the base of the giant Mount Sharp; it should get there by the end of the year.

Many people know these basic facts about Curiosity and its ongoing $2.5 billion mission on Mars. But Rod Pyle takes readers behind the scenes in his new book, "Curiosity: An Inside Look at the Mars Rover Mission and the People Who Made It Happen" (Prometheus Books, 2014).

Pyle introduces readers to some of the mission's major players, including chief scientist John Grotzinger and Mars rover maven Rob Manning, showing the human side of a robotic mission to Mars. Below is an excerpt from the book covering Curiosity's harrowing "seven minutes of terror" landing on the night of Aug. 5, 2012. [How Curiosity Looks After 2 Years on Mars (Video)]

Chapter 2 — Tango Delta: Touchdown

As you have probably surmised, John Grotzinger is not normally a nervous man. A career geologist and professor at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), he seems equally at home running a huge spaceflight project as he is in front of a class of anxious undergraduates. He jokes easily, and his explanations can be disarmingly folksy but can also turn deadly serious when explaining the relevance ofcontact metamorphism in a rock. Both are useful traits in his area of endeavor.

But tonight is different. Tonight the stakes are high indeed. Tonight, $2.5 billion of Mars rover, the aptly named Curiosity, will either land in Gale Crater to begin its twenty-four-month (one Martian year) primary mission, or pinwheel into costly wreckage across a couple hundred acres of Martian desert. Tonight will be either a validation of a decade of planning, designing, building, and launching of a wonderful era of exploration, or the likely end of America's Mars exploration program.

So tonight, Grotzinger seems as nervous as a cat on the freeway.

You would never guess it just by looking, of course; geologists don't roll like that. It can be easier to gauge the feelings of his associates in mission control at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Dozens of engineers, controllers, scientists, and other highly proficient people surround him in the final moments of the flying phase of Curiosity's mission, and some display their feelings a bit more directly. Perhaps it is because each of them has been intensely focused on a smaller part of the mission — parachute deployment, entry and guidance, pyrotechnics, software design, or one of a dozen other specialized areas. Grotzinger, as the principal scientist of the mission, must be conversant in each specialization of MSL yet also possess a more global perspective, that is, to oversee the mission once on the ground. Tonight there is not much that he can do except wait and hope.

A few consoles forward sits a man whose face is known to Mars enthusiasts worldwide but whose name may not be. Middle-aged and graying, he is nonetheless clearly still the smiling, ever-cheerful man we saw flashed so memorably across the Internet, fist-pumping the air when Mars Pathfinder landed successfully in 1997. He was thinner and darker-haired then, but the effervescent energy is still there. Rob Manning may have matured, but he is once again the chief engineer in charge of a Mars machine, and there is nowhere he would rather be. It shows.

Rob is not a professor, nor does he hold any official positions outside JPL. He has been the main machine guy for every Mars rover to date—that is his raison d'être. He is also father to two precocious daughters and plays jazz trumpet gigs in his scant spare time. Back at work, after sweating out the pioneering Pathfinder mission in 1997 and the design and landings of both Mars Exploration Rovers, Spirit and Opportunity, in 2004, he is at the crescendo of his career with Curiosity. It's been a long haul, though, and the endless hours of meetings and checkouts and visits to the cape have taken a toll. He will rest when the rover is on the ground—in one piece or in hundreds. For now his normally cheerful face shows intense concentration as he follows the data coming back from Mars. So far, Curiosity, as much a third child to him as any machine could be, is doing fine.

Down near the front sits a man whose face—or, to be more precise, whose hair—will soon be iconic. Bobak Ferdowsi sports a wild, multicolored Mohawk hairstyle, a personal statement of celebration for this momentous mission. It's like nothing we have ever seen in mission control, and within hours the Internet is alive with tweets and posts about this new phenomenon. Bobak, in his late thirties, is a handsome young man who has worked for almost a decade on MSL's launch, cruise, and approach phases. His role in these final moments of landing is largely one of quiet observation, watching data he knows are already fourteen minutes old, delayed by the huge distance between Earth and Mars. He summarized it well: "It's like taking the SAT [college entrance exam]—you've taken the test, you are done. Nobody will tell you the score right then, so you have to wait. You're nervous . . . something happening now could change the outcome of your life." And he couldn't be more correct, except that his life will change in ways far different than he expects, including a couple of hundred marriage proposals via Twitter and a future visit to the White House to meet the president and First Lady. But that is some time off, and at the moment he is fixated on the screen in front of him.

But not everyone involved with the mission can fit in mission control. A building away, Ashwin Vasavada sits, also intently eyeing a computer screen. He is, along with Joy Crisp, a deputy project scientist on MSL. He is also a spectator at this point. Curiosity carries experiments that he and Joy have helped to shepherd through the process of construction, testing, installation, and launch, as they oversee the larger science team behind the MSL mission. "I feel like I'm enabling almost 480 scientists and a spectacularly good mission with a lot of scientific integrity," he comments. "I like to put my heart and soul into making sure we do good science." Now, like Grotzinger, all he can do is watch, a helpless captive to events far away, above another world, as the much-anticipated entry, descent, and landing (or EDL) sequence begins.

Vandi Tompkins, slated to be one of a small group of rover drivers and programmers for Curiosity, is also waiting out the landing as an observer. As an engineer, she has ultimate faith in the machine and her comrades who designed it. As a PhD in advanced robotics, she also has a deep attachment to the machine in a way that few would understand. And as a woman who came to the United States from India to make her way into the stratified world of planetary exploration, she can sometimes scarcely believe her good fortune to be here, on this program, at this moment. The next few minutes may well determine her fate for the next decade.

And this is it—the by now well-known seven minutes of terror, made famous by the video of the same name that went viral a couple of months earlier. On cue, MSL spacecraft plunges into the thin Martian atmosphere after a largely uneventful journey lasting nine months. Much like war, robotic spaceflight is often characterized as long stretches of boredom followed by moments of intense terror. The spacecraft will automatically go through the intricate ballet of landing in a small target area on a planet far, far away. When it is over, the signals describing success or failure will still be making their way back to Earth at the speed of light; during landing, MSL (and the Curiosity rover ensconced within) is completely on its own. Grotzinger, Manning, Ferdowsi, Vasavada, Tompkins, and thousands of others will still be staring at computer screens, continuing to count the seconds and ticking off the milestones as if events were still unfolding. In short, regardless of Curiosity's fate, people in Pasadena and all over the world will continue watching and waiting for the signal that will free them to breathe again.

High in the skies of Mars, following a roughly equatorial trajectory, MSL hurtles toward the Martian surface. The onboard computer, a radiation-hardened version of an early-2000s Macintosh PowerPC chip, is processing incoming data like mad and adjusting flight parameters to match. A firing of a thruster here, a guidance adjustment there. There's not much time left to correct anything, though, for the guided portion of entry—where MSL glides across the skies on its heat shield, adjusting course continuously—is just about over.

On cue, the huge parachute deploys, unfurling spectacularly above the spacecraft while it is still traveling at supersonic speed. The craft begins to slow and angle toward the ground. High above, in Martian orbit, one of JPL's other robotic explorers, the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, snaps a photo of a tiny spacecraft dangling from a parachute. That it captures the lander at all is a near miracle, for it was being aimed in advance purely by sophisticated calculations performed by JPL flight engineers. The resulting image was a remarkable bit of space-age orchestration.

Down, down Curiosity drops, until—while still high in the air and in an apparent contravention of logic—it separates from the parachute. But seconds later, powerful onboard rockets fire, further slowing the spacecraft.

At JPL, a room full of men and women, mostly in their twenties and thirties, monitor the hundreds of systems and subsystems critical to a successful landing. The old folks—the ones over fifty—are mostly in the back row. This is a young person's mission.

Adam Steltzner, the forty-nine-year old rock 'n' roller primarily responsible for getting Curiosity onto the surface of Mars safely, paces like a lion on the hunt behind a row of intent controllers. He's been likened to Elvis with a doctorate in engineering, and now he monitors the consoles and the big picture. His pace quickens as the displays show MSL getting closer to Mars.

Events are occurring rapidly. Data from multiple onboard radars are guiding the machine to a landing inside Gale Crater, and within that into a landing zone called a "landing ellipse" due to the shape. It is just over five miles in width, and its long axis is twelve miles. It is the most ambitiously accurate landing attempt yet, and from what the folks back home can see, as smooth as any to date. The rocket pack/descent stage and its associated winching mechanism, collectively dubbed "sky crane," is working perfectly. In the final phase of what looks like a landing cycle designed by Rube Goldberg, or possibly Wile E. Coyote, the descent stage slows to a walking pace and sky crane begins to winch the Curiosity rover down via four cords, each about sixty feet long. It is by far the most complex interplanetary robotic undertaking in history.

Manning is at one of the rearward consoles, not quite with the old guys in the back but not with the youngsters at the front either. He's watching the system he led his team to create—not just sky crane but the whole landing system—and probably also thinking about the last-minute fixes he applied to Curiosity while it was already bolted atop the rocket, ready to launch. It was a close thing.

Al Chen is on the console as the operations lead for this critical phase of the mission and also the voice of MSL tonight. He is in his thirties, is married with three kids, and is normally a pretty unassuming guy. MSL has thrust him into the limelight, and his announcements come over the speakers in hushed, almost-unbelieving tones: "Sky crane deploying." It's JPL shorthand for "Holy s—! This damn thing works!" A collectively held breath releases and some scattered cheering issues forth, followed by applause. Then, a few moments later: "Touchdown confirmed—we're safe on Mars!" The room goes nuts as controllers, scientists, engineers, and other associated JPL'ers erupt in heartfelt cheers. In a nearby building, inside the press room, normally stoic and hardened reporters from the major TV networks, newspapers, and periodicals just lose it. It is true pandemonium. Curiosity has arrived . . . and done so to perfection.

On Mars, MSL's rocket pack, comprising the engines and the navigational unit that brought the rover to the surface, has long since detached and flown off to crash a few miles distant. After a muffled thump, silence returned to Mars.

It will later be concluded that the rover alighted about 1.5 miles from point zero, well within the landing ellipse. It's a true pinpoint landing, as close to Mount Sharp, their primary objective, as anyone dared to hope.

Once the machine is secured, a jubilant EDL team bursts forth from mission control, heading to the press room (in more normal times, JPL's auditorium), wearing matching powder-blue polo shirts and chanting "Eee-Dee-El! Eee-Dee-El!" in triumph. It is a rare moment of collective joy and outright, raw emotion for these normally reserved people as they literally dance across the university-like quad. And it is well deserved.

Grotzinger smiles broadly, hugs a few people, pumps even more hands, and prepares for the press conference soon to follow. Rob Manning is mobbed by well-wishers, smiles like the punch-drunk engineer he is (he has been at this for eight intense years and has not slept much for almost thirty-five hours), and heads off to a series of interviews. Joy and Vandi hug coworkers and then begin to think ahead. Unlike Grotzinger, they do not have the camera lights and questions of a press conference to distract their attention from the challenges that lie before them. Both return to thinking about the larger mission—the upcoming milestones needed to ensure that the rover can accomplish its primary objectives.

Bobak Ferdowsi takes a moment to check his smartphone and discovers that in the past few hours, he has become an Internet meme and instant sensation. But there is not time for that now; he has people to congratulate and a rendezvous with a pillow. Ashwin feels the glow begin to fade a bit. He is responsible for coordinating the moment-to-moment science activities of the mission, a massive job, and tomorrow things will get very busy regardless of how much—or how little—sleep he manages to get. Nonetheless, he will remember the landing as one of the high points of his life.

Hundreds of others on-lab, and hundreds more offsite, pop champagne corks and toast success tonight. They enjoy the moment, as well they should, for tomorrow engineers, scientists, and managers begin a multimonth grind known as Mars Time— their days will match Martian days, known as "sols," which add forty minutes to each twenty-four-hour Earth day. The world will soon become a surreal, time-shifted place to the bleary-eyed participants in Curiosity's mission. But tonight is for celebration.

On Mars, the dust has settled around the unmoving rover. A few clicks and whirs can be heard from the inside as the Hazcams pop open lens coverings and begin imaging the immediate surroundings. Other mechanisms restrained for landing free themselves, and heating systems power on for the cold Martian night ahead.

Curiosity has arrived, and the greatest adventure Mars has known is about to begin.

BUY "Curiosity: An Inside Look at the Mars Rover Mission and the People Who Made It Happen" >>>

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook , Twitter and Google + . The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Space.com is the premier source of space exploration, innovation and astronomy news, chronicling (and celebrating) humanity's ongoing expansion across the final frontier. Originally founded in 1999, Space.com is, and always has been, the passion of writers and editors who are space fans and also trained journalists. Our current news team consists of Editor-in-Chief Tariq Malik; Editor Hanneke Weitering, Senior Space Writer Mike Wall; Senior Writer Meghan Bartels; Senior Writer Chelsea Gohd, Senior Writer Tereza Pultarova and Staff Writer Alexander Cox, focusing on e-commerce. Senior Producer Steve Spaleta oversees our space videos, with Diana Whitcroft as our Social Media Editor.

Source: https://www.space.com/27092-curiosity-mars-rover-book-excerpt-rod-pyle.html

0 Response to "I Left My Socks on Mars Book"

Post a Comment